Did a UFO Sabotage a Cold War Missile Test? The Evidence Is Buried in the Archives

Liberation Times Opinion & Insight

Written by Geoff Cruickshank - 3 January 2025

Recent confirmations reveal U.S. government knowledge of Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP) tagging along with re-entry vehicles during missile tests.

Notable examples include the Atlas 8F missile test on 19 September 1962 and the apparent shootdown of a UAP during the Bluegill Triple Prime nuclear test on 26 October 1962.

These developments add credibility to Lieutenant Bob Jacobs' account of the ‘Big Sur’ incident on 15 September 1964.

During this event, Lieutenant Jacobs filmed a UAP interfering with the deployed Re-entry Vehicle (RV) of an ICBM test.

This was part of the Advanced Ballistic Re-Entry System (ABRES) program, using a specialized image orthicon telescope loaned from Boston University.

Following the incident, Lieutenant Jacobs was shown the footage during his debriefing and instructed by his superior officer to “never speak of it again.”

The footage is reportedly stored in the U.S. National Archives at a classified level.

Newly uncovered technical reports suggest deliberate misinformation about the missile guidance systems involved, likely to cover up the true events. Sixty years later, the footage remains classified.

If there’s nothing to hide, why is it still kept secret?

This article dives into technical data from the guidance systems used at Vandenberg Air Force Base (the Western Test Range) in 1964. It aims to show two key points:

The systems blamed for the ‘All Engine Cut Out’ command and strange trajectory issues couldn’t have caused those problems, as the official report claims.

The deactivated system was likely used as a convenient excuse to cover up what really happened—avoiding costly investigations and changes to the Atlas ICBM fleet and NASA’s Agena program. According to Lieutenant Jacobs and Major Mansmann, the real issue was interference from a “tag-along” UAP during RV separation.

To back this up, the article goes through the data from the one-page report, line by line, breaking down what it really means.

The report in question is found on page 37 of the Vandenberg Commander’s summary of Atlas missile launches from 1963-1964.

Let’s go through this, line by line.

Line 1: Classification Details

The report was originally classified as SECRET on 7 October 1964. It was later downgraded to CONFIDENTIAL on 6 November 1967 and fully declassified around 1976, following Department of Defense Directive 5200.10 (as indicated by the stamp and dates on the footer).

Line 2: Missile and Mission Details

The missile used was an Atlas D, part of the 107A weapons system, and the mission was codenamed “BUTTERFLY NET.” This test aimed to evaluate the Kwajalein Anti-Ballistic Missile radar's ability to track a Low Observable Re-entry Vehicle (LORV) and a miniature graphite model of a re-entry vehicle.

Line 3: Launch Number and Serial Number

This was Atlas D missile number 245, with the serial number 62-12432.

Line 4: Launch Timing and Conditions

The test occurred on 15 September 1964 at 15:27 GMT (8:27 AM local time at Vandenberg Air Force Base). This aligns with Lieutenant Jacobs' memory of a broad daylight launch. Sunrise that day was at 6:53 AM, meaning the launch took place under full daylight conditions. Another launch, codenamed “BUZZING BEE,” occurred later that month on 22 September at 6:08 AM local time, just before sunrise at 6:59 AM.

Lines 5-14: Countdown and Mission Purpose

The ‘BUTTERFLY NET’ mission was designed to test the flight characteristics of the LORV-3 prototype as it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. The test also included:

A Graphite Test Vehicle strapped externally.

A Scientific Passenger Pod with onboard experiments.

The LORV's hypersonic maneuvering ability in its terminal phase was also tested. A prior launch attempt on 12 September failed due to issues with the LORV’s attitude control system. Lieutenant Jacobs' recollection aligns with these details, confirming the test's focus on the RV and not on a Nike Zeus radar, which was tested a week later.

The 15 September launch was delayed to replace a faulty liquid oxygen (LOX) solenoid and fix a sticking gantry platform.

Lines 15-27: The Discrepancy in Reports

This section raises questions about discrepancies in official accounts. Reporter Eric Mishara wrote in Omni Magazine (1985) that Vandenberg's media relations stated no UAP was involved and the missile hit its target. The spokesperson, Sergeant Lorri Wray, provided these assurances.

However, technical data contradicts this narrative, pointing to potential misinformation. The General Electric Radio Tracking System (GERTS), mentioned here, was one of two systems used for Atlas D missiles. Later models used Automatic Inertial Guidance (AIG), but earlier versions like the Atlas D relied on Radio Inertial Guidance (RIG).

Even with AIG, the Range Safety Officer could issue ALL ENGINE CUT OUT (AECO) or destruct commands if necessary.

The report's explanation of the AECO event appears inconsistent with the known capabilities of the missile's guidance systems, hinting at a possible deliberate cover-up.

Starting at Line 16, the 245D report states that:

‘Telemetry data indicated that the GERTS missileborne rate beacon failed at 63.8 seconds after lift-off.

Flight effects were that error box was automatically elongated, and Navy Safety GERTS sent an automatic ALL ENGINES CUT OFF (AECO) after SUSTAINER ENGINE CUT OFF (SECO). VERNIER ENGINES CUTOFF (VECO) was never sent because of AECO.’

The issue is that multiple official documents confirm the GERTS missile-borne rate beacon was installed but deactivated on all Atlas D series missiles.

This means the AECO signal could not have been sent by the Western Missile Range GERTS at Vandenberg Air Force Base —or even by a so-called ‘Navy Safety GERTS’ supposedly located downrange.

So, why does the official flight test report claim otherwise?

In the early days of the Atlas D missile system, long before the arrival of Automatic Inertial Guidance (AIG), engineers ran into a frustrating issue: the missile’s rate beacons were easily overwhelmed by noisy AM signals from its own onboard systems.

They tried to fix it with a smoothing filter (ECR A3-41), but the problems didn’t go away.

Velocity calculations from the P station and Q station were still inconsistent, and the system struggled to perform as expected.

This was more than just a technical glitch—it was a big deal.

The fledgling AIG system needed pinpoint accuracy to issue critical commands like Booster Engine Cut Out (BECO), Sustainer Engine Cut Out (SECO), and Vernier Engine Cut Out (VECO).

These commands ensured the Re-entry Vehicle (RV) would follow the precise trajectory needed for a successful mission.

When the data didn’t add up, engineers had to rely on the backup Radio Inertial Guidance (RIG) system.

To make matters even more pressing, the Atlas D missile wasn’t just any rocket—it was the backbone of Project Mercury, America’s first attempt to put humans in space.

Fixing these rate beacon issues wasn’t just important—it was essential.

Although the MOD III system carried the ‘General Electric’ name, it was actually the brainchild of Isaac Aurbach, an engineer from Burroughs Corporation.

Aurbach was the genius behind the MOD I, II, and III systems, which were rolled out at major test and operational sites: Cape Canaveral’s Eastern Test Range, Vandenberg’s Western Test Range, and Atlas ICBM facilities at Offutt Air Force Base, Warren Air Force Base, and a training unit at Kessler Air Force Base.

These systems were groundbreaking—they were the first missile guidance computers to use transistors instead of vacuum tubes, revolutionizing the technology.

But the innovation came with its challenges.

Persistent errors in the Rate Subsystem during several Atlas D flights led General Electric engineers to suspect the Burroughs computing architecture and the quality control of the transistors themselves.

To tackle the problem, they used a divide and conquer strategy, developing a modified version of the MOD III system.

This new version, named the General Electric Radio Tracking System (GERTS), featured a Harris 5120/4 computing core and focused exclusively on missile tracking.

The idea was to bypass the noisy rate data and check the MOD III system’s accuracy.

To smooth out inconsistencies, engineers added weighted numerical filters to the logic—but with limited success.

Importantly, while GERTS modules on Atlas D missiles included a rate beacon, both the beacon and the ground processing systems were deactivated.

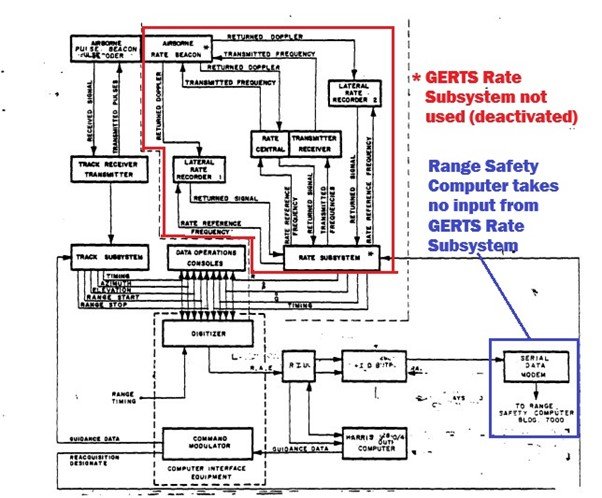

The system wasn’t even connected to the Range Safety Officer’s command console, as marked by an asterisk in the original diagrams.

In short, no GERTS system—whether on the ground or ship-borne—could have been responsible for sending the AECO command, raising more questions about the official explanation.

The exact whereabouts of the mysterious ‘Navy Safety GERTS’ remain a puzzle.

Burroughs Corporation only built 12 units of the MOD III system, and of those, just 9 reached Initial Operating Capability (IOC):

Unit A-3 went to Kessler Air Force Base as a training aid

Unit A-4 was delivered to Vandenberg Air Force Base in June 1959 to support the 576th Strategic Missile Squadron

Units A-5, A-6, A-10, A-11, and A-12 were sent to Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming

Units A-7, A-8, and A-9 were installed at Strategic Air Command HQ at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska.

Since the GERTS system was a modified version of the MOD III, its exact components and supposed location for the ‘Navy Safety GERTS’ are unclear.

There’s no evidence of it being installed at key locations like the Western Test Range Mid-Course Tracking Facility at Kaena Point, Hawaii, or onboard the USAS American Mariner (T-AGM-12), a DAMP ship operating in the Western Test Range area in 1964.

In fact, according to Page 16 of the Land Based Systems manual, there’s only one confirmed GERTS installation at Vandenberg Air Force Base, leaving the Navy’s involvement—or even the system’s existence—highly questionable.

The supposed Navy Safety GERTS seems more like a red herring, likely designed to mislead anyone without the proper ‘Need to Know’ clearance about the true cause of the incident.

Historical records don’t indicate the existence of the subsystem that reportedly triggered the AECO command.

Adding to the mystery, a February 1964 document titled ‘Utilization of Deactivated Missile Guidance Systems’ notes that the MOD III tracking and rate systems were nearing retirement.

The newer Atlas E and F series missiles had already adopted Automatic Inertial Guidance (AIG), making the older systems redundant.

The document suggests potential reuse of the decommissioned systems in other missile or satellite programs.

Premature Engine Shutdowns

Lines 20–23 of the report compare the planned and actual timings for the Booster Engine Cut Out (BECO), Sustainer Engine Cut Out (SECO), and Vernier Engine Cut Out (VECO). The Vernier engines shut down 18.4 seconds earlier than planned. For reference, data from the Atlas 8F test on 19 September 1962 (uploaded by the Office of the Secretary of Defense under “UAP”) shows that at SECO, the Atlas 8F had a velocity of 20,140 feet per second (Mach 18).

Premature Re-entry Vehicle Separation

Lines 24–25 reveal that the automated system onboard the Atlas 245D initiated Re-entry Vehicle (RV) separation just 3.05 seconds after VECO, also 18.4 seconds too early. This left insufficient time for the velocity to decay, making it impossible for the RV to achieve the precise trajectory required. Additionally, the Graphite Test Vehicle was deployed early, likely disintegrating due to the extreme conditions.

Retrorocket Timings

Lines 26–27 detail the HIRS Pitch and Retro timings, which control the High Impulse Retrorocket System responsible for redirecting the spent tankage away from the RV and other experiments. Due to the AECO incident, these retrorockets also fired earlier than planned, compounding the trajectory issues.

Tracking the Missile

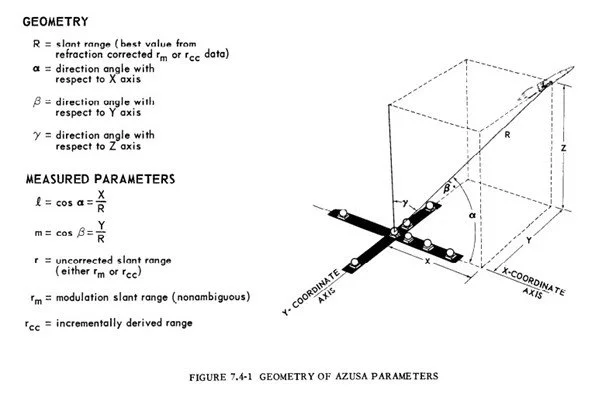

Lines 28-30 of the report notes that the MOD III Guidance System successfully acquired the missile in flight ‘in the first cube.’ This refers to the specific area of coverage provided by the ground-based tracking equipment. Although the accompanying image is from the Eastern Test Range (Cape Canaveral), it illustrates how the ‘cube’ represents the tracking zone used at Vandenberg Air Force Base.

GERTS and the AECO Signal

The report mentions that the GERTS system acquired the tracking pulse beacon in the first cube. However, it also notes that the rate beacon began malfunctioning at 61.2 seconds and completely failed at 63.8 seconds, supposedly triggering the AECO signal to the Range Safety Officer console.

This claim doesn’t align with the technical parameters of the GERTS system. Numerous documents explicitly state that the GERTS Rate Subsystem was permanently deactivated and wasn’t even connected to the Missile Flight Control Officer/Range Safety Officer console. This raises further doubts about the official explanation.

RV Miss Distance

Lines 31–33 describe the miss distance for the Re-entry Vehicle (RV) at the Kwajalein Test Site’s splash zone, calculated by both the MOD III and GERTS systems. These figures confirm that both systems were active during the flight of Atlas 245D.

However, the data reveals a significant discrepancy—several nautical miles— between the two systems' results. This inconsistency suggests that the troubleshooting measures by General Electric engineers had mixed success and casts doubt on Sergeant Lorri Wray’s claim that the RV ‘successfully hit its target.’

In reality, the RV splashed well short of the designated area.

Remarks on the RV and Onboard Experiments

Lines 34–41 highlight details about the Low Observable Re-entry Vehicle (LORV) and additional experiments. The RV is described as having a bi-conic configuration with a ‘two cone-cylinder-flare’ design, similar to the GE Mark III Re-entry Vehicle. This section also emphasizes the experimental and complex nature of the mission.

As described in Lines 24–25, the Re-entry Vehicle (RV) separated from the missile body 4.15 seconds after the Sustainer Engine Cut Off (SECO), reaching a maximum velocity of around 20,000 feet per second.

However, without the precise burns of the Vernier engines to adjust its attitude and pitch, it’s highly likely that the long, slender RV began tumbling almost immediately after separation—just as Lieutenant Jacobs claimed in the image orthicon footage he reviewed.

The complex interplay between the RV's angle, velocity vectors, and angle of attack during a normal separation would have made stable flight nearly impossible.

For the BUTTERFLY NET re-entry vehicle, this would have been true even if it had its own internal attitude control system.

These conditions strongly align with Lieutenant Jacobs’ account of what transpired during the test.

The Premature Deployment of Onboard Payloads

The Graphite Test Vehicle, attached to Quadrant III of the missile body, was ejected prematurely into a high-friction, Mach 18 environment for which it was not designed.

It likely disintegrated immediately, potentially explaining why Lieutenant Jacobs described seeing a ‘chaff’-like radar decoy in the footage shortly after the Re-entry Vehicle (RV) separated.

Meanwhile, the Scientific Passenger Pod (SPP), attached to Quadrant II, contained two experiments by the USAF Office of Aerospace Research (OAR).

However, due to the AECO command, the SPP was either improperly deployed or not deployed at all.

Its intended purpose was to remain with the missile tankage after RV separation, supported by the HIRS retro-rockets, to ensure the spent missile components followed a safe trajectory. The contents of the OAR experiments remain unknown.

Despite these complications, the report claims the Atlas 245D mission achieved “very good” radar, telemetry, and optical coverage—an assertion that appears questionable when contrasted with the technical evidence.

Conflicting Accounts and Publicly Available Documents

There are clear contradictions in the reporting of the Atlas 245D flight. One report states that the third stage propulsion system (Vernier engines) failed, leading to premature payload deployment and trajectory issues.

However, a 2014 blog post by Tim Printy, citing a document titled ‘Progress Report for September 1964: Nike-X Weapons System’, suggests the mission was a success.

According to this version, the RV, graphite test vehicle, and SPP were tracked as planned, with no mention of interference by an unknown object.

The conflicting narratives raise a fundamental question: Which report is accurate?

The answer likely lies in the classified footage of the 15 September 1964 launch, stored in the National Archives.

Efforts to Declassify the Footage

In 2019, Joseph Durso filed a Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) request for documents, including the ‘Nike-X Report of Progress’ from October 1964.

The National Archives confirmed possession of the footage but stated it had not undergone a declassification review by the originating agency (the U.S. Army) since its creation. No further updates have been provided on this request since December 2019.

Further investigation and transparency from relevant agencies, such as the Pentagon’s UAP office (AARO), could finally shed light on this decades-old mystery.

For more information on Tim Printy’s report, refer to his blog here. Details on the MDR request can be found here.